Commentaries /

Federal Fall Economic Statement 2023: A Place(holder) in Time

Federal Fall Economic Statement 2023: A Place(holder) in Time

Economic Pain Delayed, but a Slightly Better Outlook by the End of the Projection

Stephen Tapp

In the Federal Government’s 2023 Fall Economic Statement (FES), private-sector forecasters now expect Canada to avoid a recession this year. While that’s great news, unfortunately, the economic resilience to-date merely delays some inevitable pain: facing higher inflation — and therefore higher interest rates — economic growth is now expected to slow to a crawl in 2024 (rather than in 2023), while Canada’s living standards continue to slip. Meanwhile the pain of high inflation isn’t going away quickly; forecasters don’t expect inflation to return to target until the end of 2024.

Federal fiscal policy largely avoided fanning the flames of inflation by not introducing new big-ticket spending measures. Nonetheless, even after accounting for the FES, monetary and fiscal policy in Canada will continue to work at cross purposes in the fight against inflation in the year ahead.

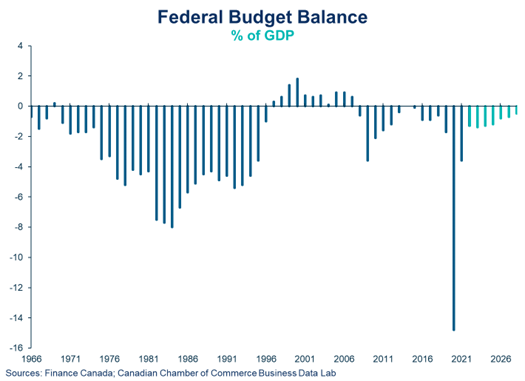

As with consumers and businesses, the modest deterioration in the federal government’s fiscal outlook largely reflects the increasing squeeze coming from higher debt servicing costs. In this challenging context, the government’s fiscal anchors and objectives continue to evolve. The latest material addition to the fiscal plan is to keep federal deficits below 1% of GDP starting in 2026 (i.e., after the next Federal election), which doesn’t leave much fiscal room, given the current outlook.

Stephen Tapp, Chief Economist, Canadian Chamber of Commerce

KEY ECONOMIC TAKEAWAYS

Economic Pain Delayed, but a Slightly Better Outlook by the End of the Projection

Back in Budget 2023, forecasters expected Canada to suffer a mild recession this year. Since then, we’ve had two modestly negative quarters out of the last three, however, a strong burst of growth in the first quarter (due to a hiring boom coupled with unseasonably warm weather), will likely deliver better growth in 2023 than was previously expected. (Real GDP growth in 2023 is now expected to be 1.1% in the Fall Economic Statement, FES, vs. only 0.3% in Budget 2023).

The “good news”, then, is that in this update, forecasters now expect Canada to avoid a recession in 2023, so the economic starting point for the projection has improved.

The “bad news”, though, is that because the economy has not yet fallen into recession, and because inflation has remained higher than expected or desired, the Bank of Canada raised its policy interest rate by another 0.5% this summer to 5% to try to bring inflation back to target.

As a result of this move and other global factors, financial markets are now pricing in higher interest rates over the next few years. This will not only raise borrowing costs for consumers and businesses as well as the government, but will also slow growth to a crawl next year. (Real GDP in 2024 is expected to be only 0.4% in the FES vs. 1.5% in Budget 2023 — so in effect, the inevitable slowdown was merely pushed out a year).

Given strong population growth due to high immigration (currently running around 3% annually), this means Canada’s living standards will continue to decline in the near term, as real GDP per capita continues to fall.

Meanwhile, the pain of high inflation is not going away quickly. Forecasters don’t expect inflation to return to the Bank of Canada’s 2% target until the end of 2024.

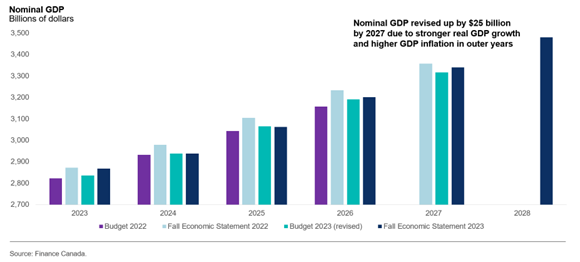

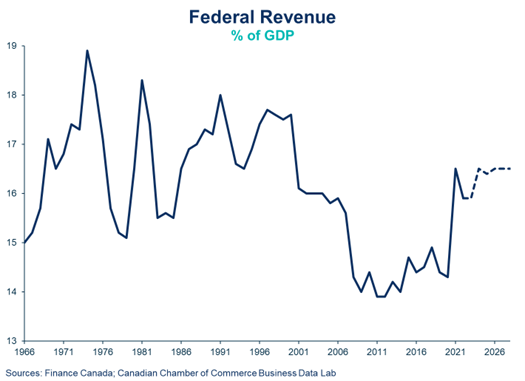

Taking all these factors together, the somewhat surprising upshot in the FES, is that the path for Canada’s nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP, the broadest measure of the government’s tax base) was revised up relative to Budget 2023.

This reflects the positive growth shock in year one, followed by the delayed slowdown in years two and three, followed by slightly stronger real GDP growth and higher GDP inflation in the outer years of the projection.

New Fiscal Measures: Not Making Inflation Worse, but Not Making it Better Either

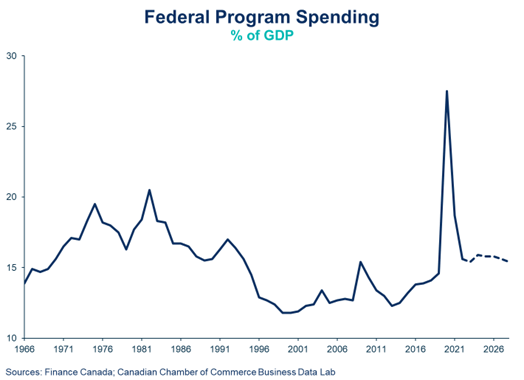

The FES adds $20.8 billion in net new measures over the projection (averaging $3.5 billion annually). Since many of these were previously announced, and are unlikely to have significant economic impacts in the near term, I won’t review them here. (For those interested, the Chamber’s policy team provides their insights here.)

The Finance Minister characterized the FES as a “responsible fiscal plan” that made a “conscious decision to avoid pouring fuel on the fire of inflation,” and evidently, the net federal fiscal impulse in the FES is not large. However, as Bank of Canada’s latest Monetary Policy Report showed, spending across all levels of government in Canada “contributes materially to growth, averaging 2.5% through 2024, somewhat above potential output growth”. Scotiabank estimates that the overall fiscal policy response since the pandemic has likely contributed roughly 2% of the 4.75% increase in the Bank’s policy interest rate over the hiking cycle.

In other words, even after the FES, monetary and fiscal policy in Canada will continue to work at cross purposes in the fight against inflation. It’s one thing not to add much more to federal spending, but that’s not the same thing as removing some near-term spending. That latter would help the Bank of Canada bring inflation back to target sooner, which would allow interest rates to fall faster, and economic growth to ultimately pick up faster.

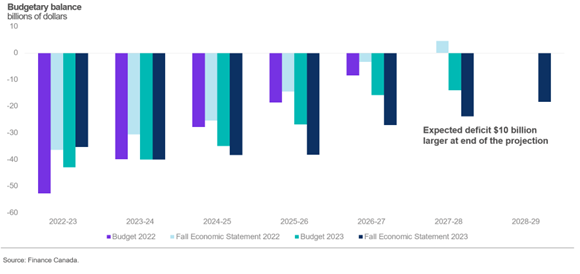

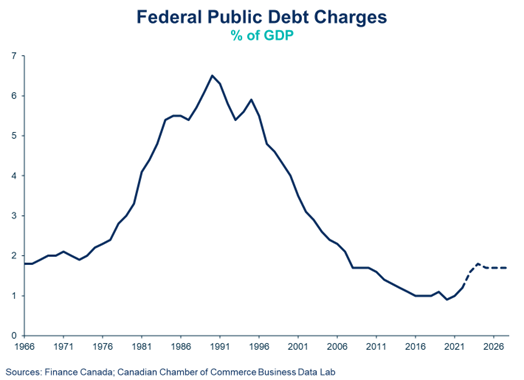

Deficits: Given better-than-expected economic outcomes noted above, the deficit last fiscal year came in better than expected in Budget 2023. However, the deficit track in the next fiscal year and beyond is worse, with the federal deficit expected to be $10 billion larger by the end of the projection. Much of the fiscal deterioration reflects higher public debt charges (due to higher interest rates, as debt charges grew from 7.8% of total revenue last fiscal year to 10.6% by the end of the projection), and to a lesser extent, higher transfer payments for inflation-indexed benefits.

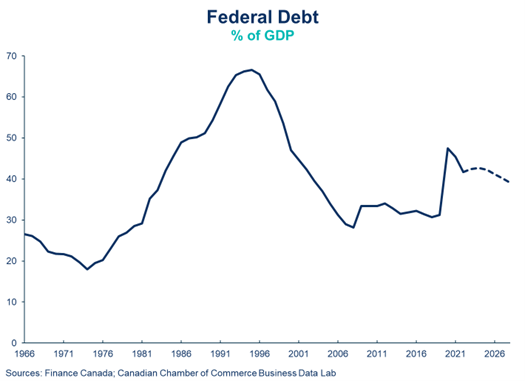

Debt: Federal debt increases by $189 billion over the projection to $1.4 trillion five years out. As a share of GDP, federal debt starts at 42%, and is expected to rise slightly over the course of the next three years, before ending the forecast modestly better at 39% in 2028-29.

Fiscal anchors: The government’s fiscal objectives continue to evolve as circumstances change. Recall that Budget 2023 had dropped any previous reference to eliminating the deficit (one part of the fiscal plan in the FES 2022 was to “unwind COVID-19-related deficits”).

The government continues to focus on reducing the federal debt-to-GDP ratio over the medium term. However, this constraint has been modified slightly to permit temporary increases for two fiscal years. There’s also new language for this fiscal year about having a better deficit than was expected in Budget 2023 ($40.1B).

The newest fiscal objective is to keep federal deficits below 1% of GDP, starting in 2026-27. Since nominal GDP is expected to be around $3.2 trillion by that time, this would allow deficits of roughly $32 billion annually. Given the status quo outlook, that would not leave much additional fiscal room for new big-ticket programs (e.g., a national pharmacare program — absent a significant reallocation of existing spending commitments, or an increase in taxes).

More Fiscal Charts

Other Commentaries

Oct 19, 2022

September 2022 Consumer Price Index data: Food and services prices still rising, no progress on core inflation

Sep 20, 2022

August 2022 Consumer Price Index data: Finally some good news on Canadian inflation.

Aug 16, 2022